Charles River Is In Trouble

Their moat is made of dead animals – but now the rats are leaving. Can Charles River take the hit?

Charles River Laboratories is in trouble.

If you’ve been following the FDA’s slow-motion reimagining of how drugs get approved in this country, you’ll know that last week, the agency dropped a seismic update: they’re planning to gradually phase out preclinical animal studies for monoclonal antibody BLAs. Not reduce. Not refine. Phase out—as in, eliminate.

The new guidelines—quietly slipped out in a dense, 11-page roadmap PDF—lay out a path for sponsors to start submitting INDs and BLAs for mAbs without the usual mouse-to-monkey toxicology gauntlet. Instead, developers can lean on organoids, organ-on-chip systems, human-derived cell models, AI simulations—what the FDA calls “New Approach Methodologies,” or NAMs. What Charles River might, internally, call a direct threat to their business model.

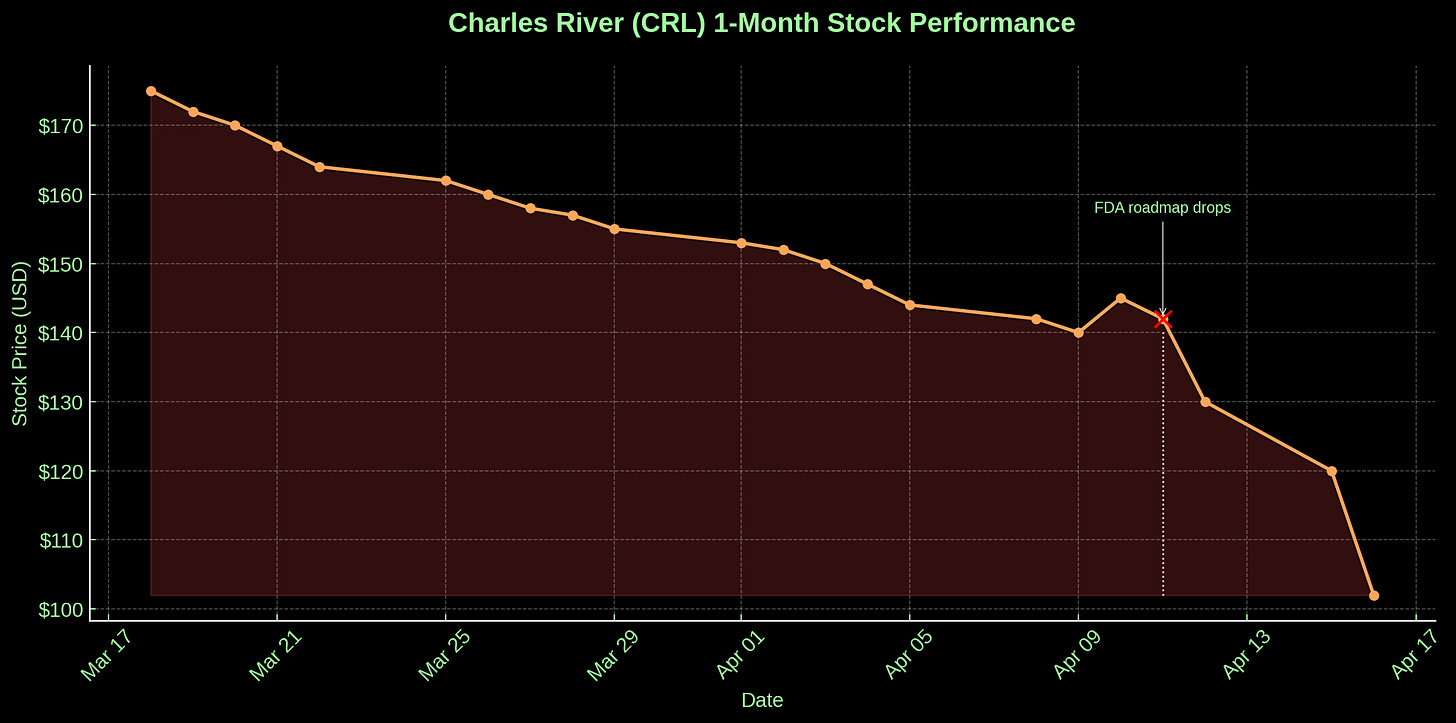

Cue the reaction:

Charles River’s stock ($CRL), already dragging under the weight of a sluggish biotech cycle and the lingering stink of a Cambodian primate import scandal (a subplot best filed under Primategate), went into free fall. Not a dip. A crash. The kind of sickening vertical drop that gives hedge fund analysts nosebleeds and makes Reddit traders open their Robinhood apps mid-coitus. Twenty percent, gone in a flash. Analysts downgraded. Shareholders balked. Pundits murmured “existential.”

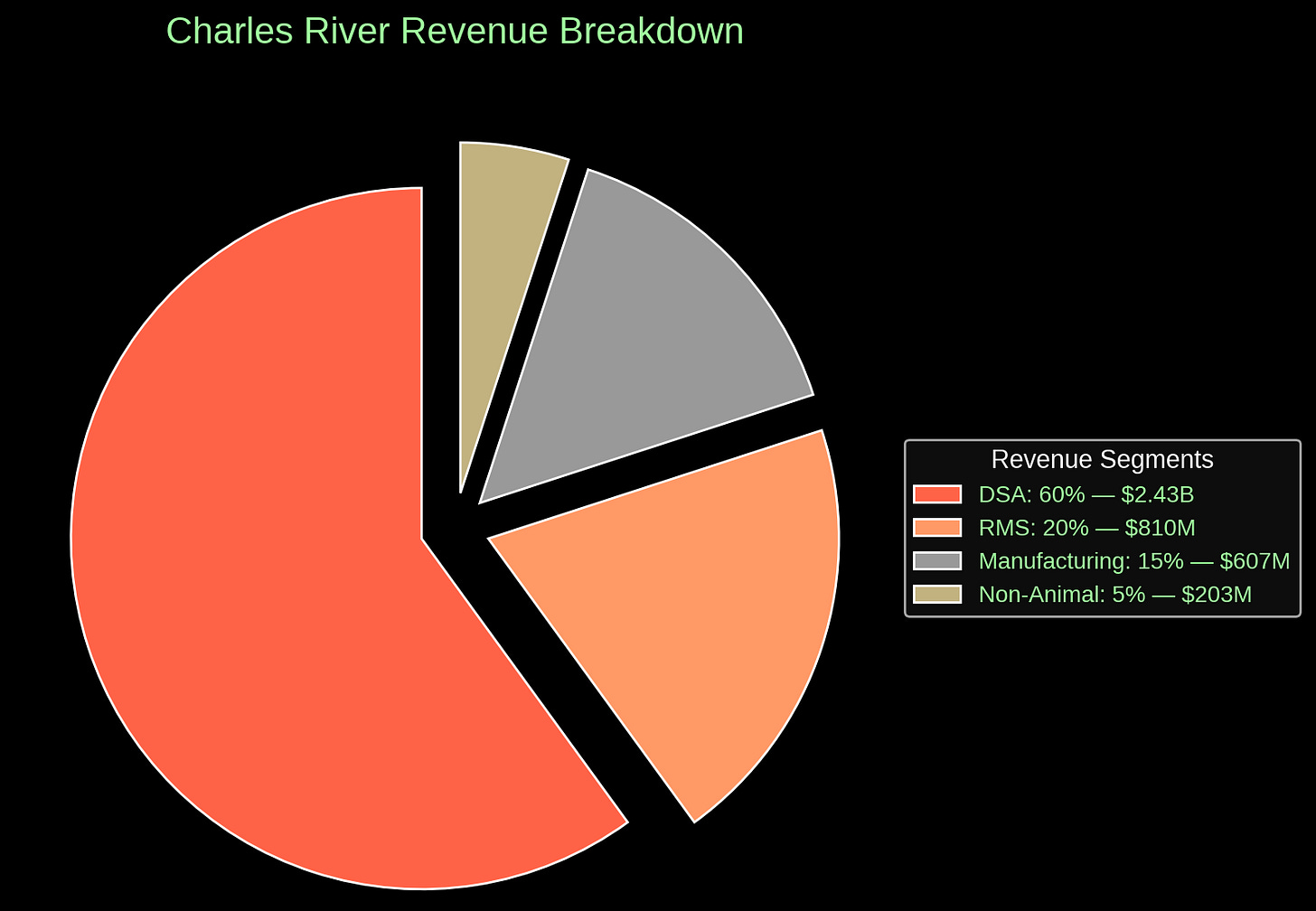

And why the panic? Because Charles River is animal testing.

We’re talking about a company that—by its own admission—derives something like 80% of its revenue from two business lines: one that literally breeds animals for lab use (RMS, the Research Models & Services division) and one that conducts the preclinical studies (DSA, Discovery & Safety Assessment) that have, for most of modern pharmaceutical history, relied on those animals to prove a compound’s worth.

For most of modern pharmaceutical history, Charles River has been the god of rats, full stop. And now, the FDA—the only god that matters more—is questioning whether rats are needed at all.

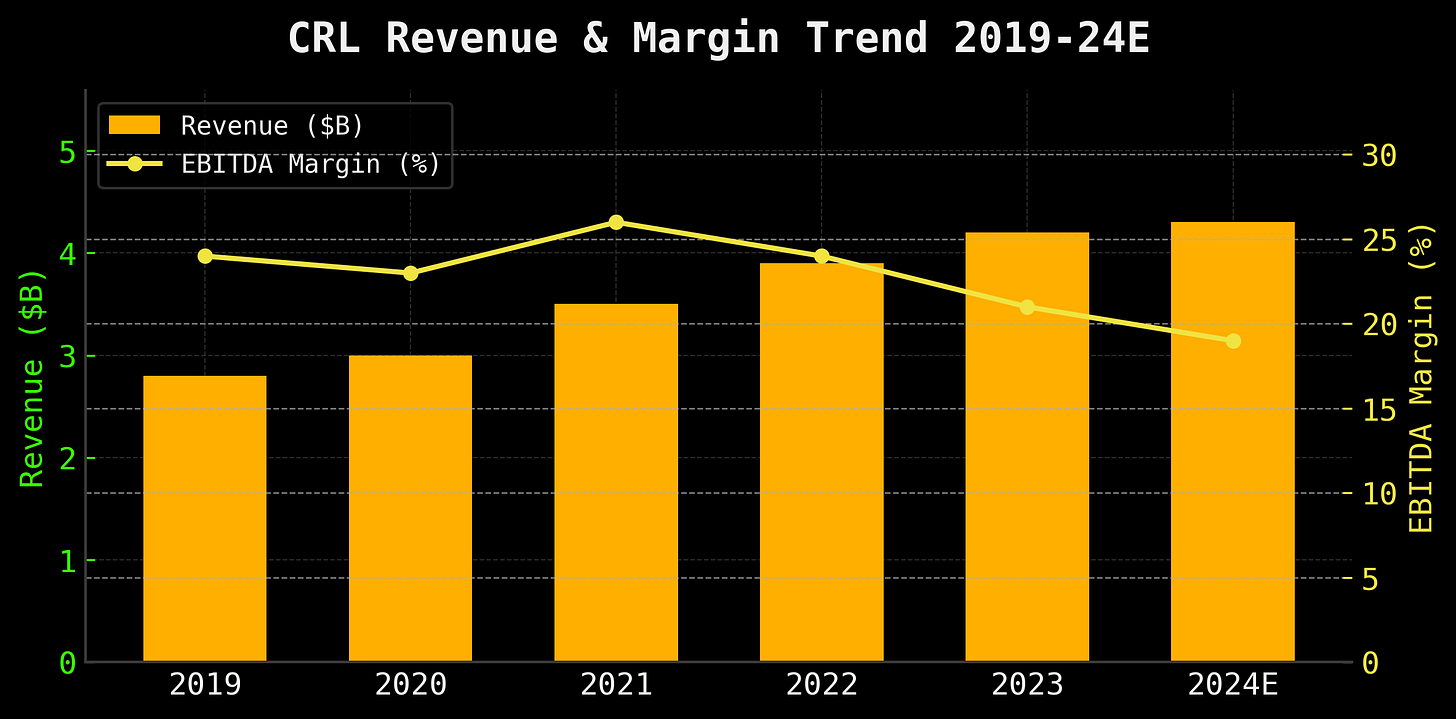

But let’s talk numbers. Because no matter how philosophical we get about the ethics of rat suffering or the beauty of liver organoids––this is a public company. And public companies live and die by margins, multiples, and whether sell-side analysts can look at a 10-K without vomiting.

Before the FDA’s announcement, CRL wasn’t in freefall. It was more like a well-fed prizefighter getting winded in round seven. As per their 2024 10-K, they were already managing damage:

A moderate-to-heavy debt load, with enterprise value exceeding market cap by $2.5B.

2024 adjusted EBITDA of ~$570M, with margins around 14%, down from a healthier 17–20% in the pre-scandal years.

A guidance of 4.5–7% revenue decline in 2025, even before the FDA blindsided them with the NAM roadmap.

Why the drop? Blame it on a few converging disasters:

The Cambodian primate import scandal—a weird, semi-dark episode involving questions about whether Charles River’s non-human primates (NHPs) were actually wild-caught, which led to halted imports, skyrocketing costs, and a whole bunch of canceled studies.

The biotech downturn—smaller biopharmas, already struggling with higher interest rates and tighter capital, cut back on their R&D budgets, which hit Charles River’s bread and butter: outsourced preclinical studies.

General inflationary pressure—energy, logistics, and lab technician salaries don't pay themselves.

To triage the bleeding, Charles River initiated cost-saving measures and restructuring in late 2024—essentially streamlining their site network and trimming fat. Management has claimed that these efforts would offset the projected 4.5–7% decline in revenue for 2025, even before the FDA pulled out the rug. They suggested profitability would only be “modestly” affected—corporate-speak for “we’re not panicking yet, please don’t tank our stock.”

And so far, their liquidity and free cash flow remain solid. They’re not at risk of missing payroll or defaulting on debt. They’ve continued investing—selectively—in AI modeling, microphysiological systems, and even a few tuck-in acquisitions to hedge the NAM transition. The war chest isn’t bottomless, but it’s not empty either.

Alas, Wall Street doesn’t care about “modest” hits: it cares about growth. It cares about durability. And CRL’s valuation metrics have collapsed as a result of perceived structural decline. Just look at how they stack up next to peers:

So: CRL is trading like a distressed asset, not because they’re bankrupt or losing money, but because the market is pricing in risk of obsolescence. A ~7.6× EV/EBITDA multiple is what you’d assign to a company with fundamental business model decay. And maybe that’s true. But it also means: if CRL survives the pivot, the multiple has room to double.

Compare that to Wuxi AppTec, whose multiples remain buoyant despite geopolitical risk and much more regulatory opacity in China. Or Medpace, which doesn’t touch preclinical at all and is thus being rewarded with premium pricing for the sin of staying downstream. CRL looks cheap—if it’s not marching straight into a structural meat grinder.

To fight this, they’ve been restructuring; cutting costs; consolidating sites. They’d launched something called AMAP (Alternative Methods Advancement Project), a mildly Orwellian acronym that signaled at least an awareness of the industry’s pivot toward non-animal models: organoids, chips, algorithms. There were press releases with photos of smiling scientists peering into microscopes and quotes about the “future of preclinical science.” In other words, they weren’t blind. They saw it coming. But they also still had millions of rats. And facilities built for rats. And a profit model engineered—genetically, almost—for rats. The main storyline was still: give us your compound, we’ll test it on a bunch of rodents and monkeys, and hand you a packet to submit to FDA.

Now the question is: can they pivot fast enough? And here’s where it gets awkward—because the numbers say: maybe, but not convincingly.

Cap‑ex tells the truth. Charles River’s FY24 guidance earmarks $1.05 billion in total capital expenditures.1 Our back-of-the-envelope split:

$520 M to maintain and expand animal facilities. (Translation: keep the rats alive.)

$160 M toward NAM infrastructure: organoids, organ-on-chip platforms, AI tox prediction.

The rest? IT, admin, and other CRO verticals.

That’s ~15% of spend chasing the future, while ~50% is defending the past. Which tells you exactly how this company is hedging its own obituary.

The FDA’s move has shoved Charles River into a liminal state: not yet obsolete, not yet retooled. And the window to retool is shrinking.

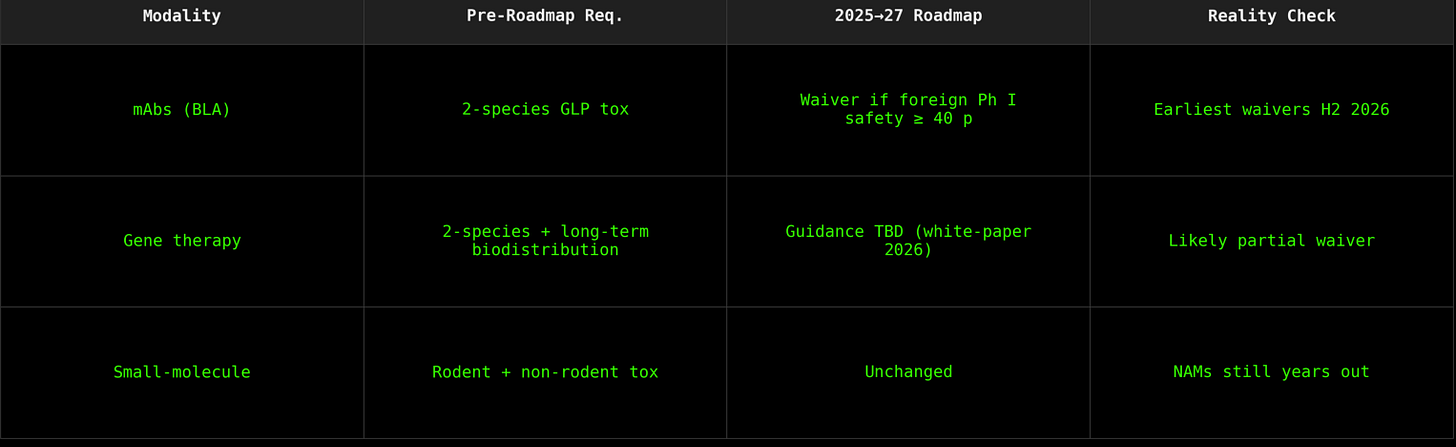

From a biotech-operator perspective, here’s the reality check on where NAMs actually stand—and what the FDA’s roadmap really enables:

So what?

If you're a hedge fund: tighten your grip on those leverage covenants—if EBITDA dips below $500M, the 2026 notes start to squeak.2

If you're a biotech operator: start budgeting for NAM tox pilots. CRL will gladly rent you their soon-to-be-surplus capacity at cut-rate margins.3

If you're in the generalist/ethics crowd: no, this isn’t vegan utopia tomorrow. Think attrition curve, not guillotine.

So what’s left for CRL? The scenarios.

Three paths. All risky. Only one ends in reinvention.

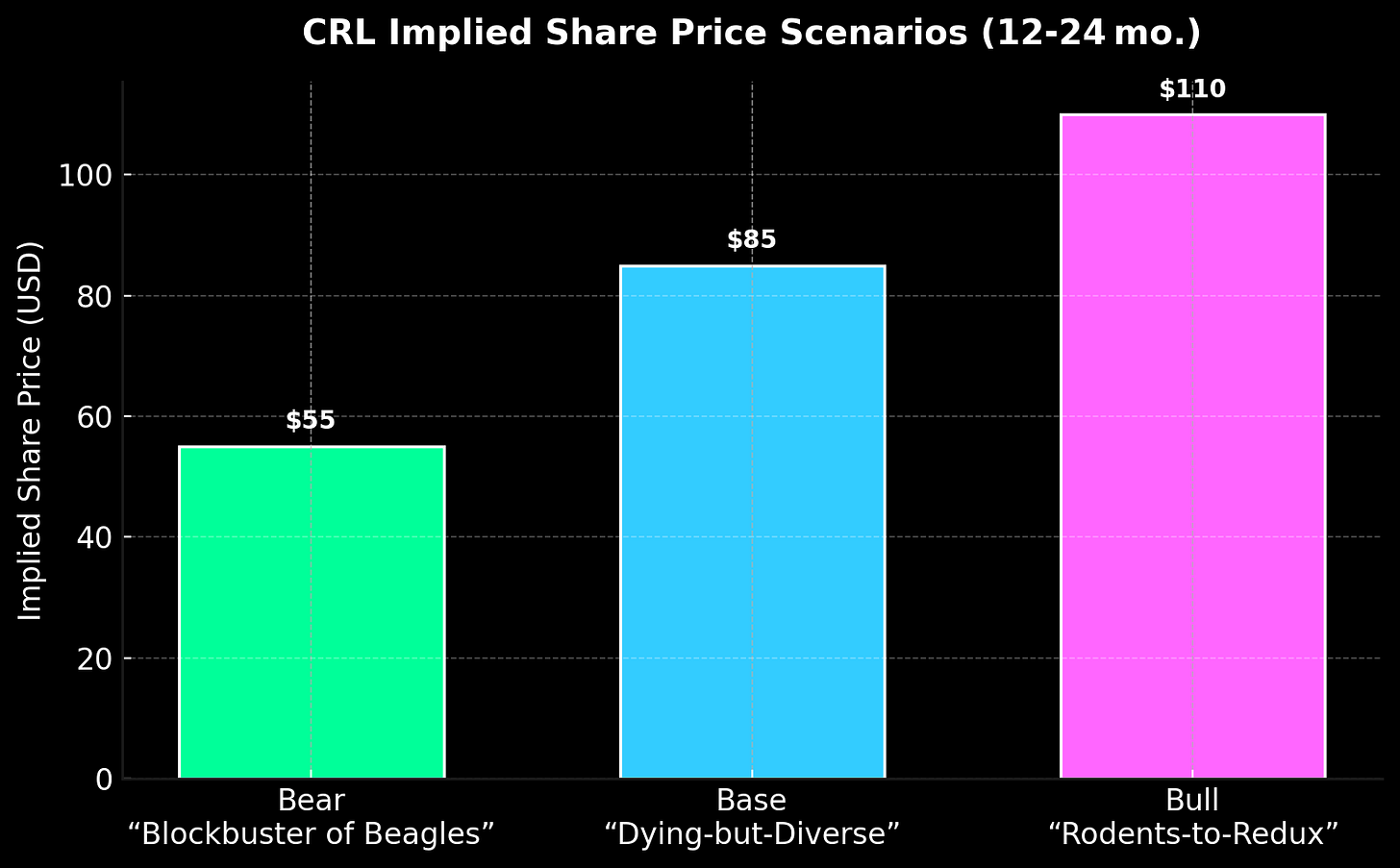

Each path has a nickname:

Bear case – "Blockbuster of Beagles": NAMs prove out fast. CRL is left renting VHS tapes of rodent data.

Base case – "Dying‑but‑Diverse": Gradual cannibalization. Manufacturing & microbiology soften the arterial bleed.

Bull case – "Rodents‑to‑Redux": FDA slows its roll. CRL rebrands as the Oracle of NAM validation; rats get severance.

Valuation-wise, slap 8×/10×/12× EBITDA multiples on those scenario lines, and you land at $55 / $85 / $110 per share. At ~$80 today, the market is effectively saying: “Show me the pivot.”

Because right now, CRL is standing at that junction. And the market’s betting they don’t make the turn. But if they do, this might just be one of those rare moments when a company staring down structural obsolescence manages to rewrite its role in the story.

The Problem Isn’t the Rats. It’s the Business Model

The question hanging over Charles River isn’t just: Will they lose revenue if animal testing goes away? It’s: What kind of company are they, if it does?

Because there’s a version of the future where Charles River still exists, still runs studies, still makes money—but becomes a kind of mid-century curiosity. A legacy provider. The company that used to breed rats but now mostly consults on how to train your AI model to simulate hepatotoxicity. Like a Blockbuster that survived the apocalypse by pivoting to metadata services for Netflix (or a Blackberry who pivots to cyber security from phones). Still here. Technically. But not exactly in command.

This isn’t some fringe fantasy. The FDA’s new stance isn’t just about ethics or shiny organoids - it’s about control. About who defines what counts as evidence in drug development. For decades, Charles River made its money knowing how to generate the kind of data the FDA liked. The necropsies, the dose-response curves, the GLP-compliant rodent mortality tables. That knowledge—down to the language, the formatting, the politics of a submission packet—was the moat. The moat was made of dead animals.

But NAMs don’t care about cages or legacy processes. They care about data architecture, human tissue fidelity, AI-validated predictivity. And for the first time in its history, Charles River is being asked to compete not with other CROs, but with entirely different species of company—bio-AI hybrids, synthetic biology startups, machine learning platforms with no interest in beagles and no sunk cost in vivariums.

The market sees this, and that’s why CRL’s valuation cratered. Not because they're losing money now, but because 80% of their revenue is tied to a paradigm the FDA just put on slow-drip hospice. You don’t get the cash-compounder multiple when your core deliverable might be irrelevant in five years.

And yes, CRL is trying. They’ve launched initiatives - joining an organ-on-chip consortium, partnering with Sanofi on NAMs, and so on. But here’s the problem: their infrastructure—literally and figuratively—is built for rats. Their labs, their processes, their staffing, their regulatory machinery—it's all optimized for a world where mice are the gold standard and non-human primates are the last line of preclinical defense.

So you end up with this weird, liminal moment: a company with billions in physical assets that may soon be half-relevant, and a bunch of cautious institutional investors trying to figure out if this is terminal decline or mispriced future-forward pivot play.

Because this isn’t just a technological transition; it’s ontological. The reason Charles River exists—their entire corporate cosmology—is being rewritten.

Estimated allocation based on Charles River’s 2024 earnings guidance and management commentary (i.e., the mentioning of investing $200 over the past 4 years in NAMs R&D). While the company does not disclose exact CapEx by division, CRL stated that a “significant portion” would go toward expanding RMS and DSA capacity—i.e., animal facilities. Investments in NAM infrastructure (organoids, AI tox platforms, microphysiological systems) were described as “strategic” and “long-term,” implying a smaller allocation. These figures are directional estimates, not line-item disclosures.

EBITDA under $500M = debt trouble. Charles River has notes maturing in 2026. If their earnings dip too far below ~$500M, they risk violating debt covenants—those fine-print rules that lenders use to keep companies on a leash. If breached, CRL might be forced to refinance under worse terms, just as their core business is destabilizing. Hedge funds: this is the number to watch.

Overbuilt NAM capacity = biotech discount. As CRL scrambles to modernize, they’re building labs for organoids, AI tox, and chip models—but customer demand hasn’t caught up yet. If you’re a biotech exec, this means you can run NAM pilot studies through CRL at a relative bargain. They need you more than you need them (for now).