Cook-Deegan got it right.

In 2015, Robert Cook-Deegan asked whether the NIH had “lost its halo”. It was a gentle provocation, posed in the syntax of a think piece, but it’s cut deeper than I think even he realized at the time. Because what he was really pointing at—beneath the policy analysis and institutional memory—was a kind of spiritual drift. A loss not of function, but of narrative. A loss of belief.

I came to this question thinking I was going to say something clever. Something clean. For the past few weeks, I set out to write a piece that would answer that - or at least take a swing at it. I wanted to point to inefficiencies, champion the Common Fund, defend the underloved intramural research program, maybe even rank the NIH institutes by ROI like it was a college football season, condemn redundancy, gently question the ROI of certain long-funded diseases, and then call it a day.

But here’s the thing I can’t shake: the deeper I went, the more it all started to feel... epistemically slippery––like trying to do calculus on fog. The NIH doesn’t let you call it a day. Not really.

Because the deeper I got, the more the whole thing started to feel unchartable. Not inefficient, exactly—though of course some of it is. More like... pre-modern. Mythic. The NIH is 27 institutes, yes, but it’s also a mood, a political artifact, a bureaucratic philosophy, a memory machine, a hedge against future disease, a conveyor belt of postdocs, and a deeply human set of judgments wrapped in scientific drag. It doesn’t behave like a portfolio; it behaves like a time-lapsed cathedral made of overlapping bets and shifting incentives. It metabolizes time differently. It stores risk. It makes moves across generations…

…Try to tell that story in a budget hearing.

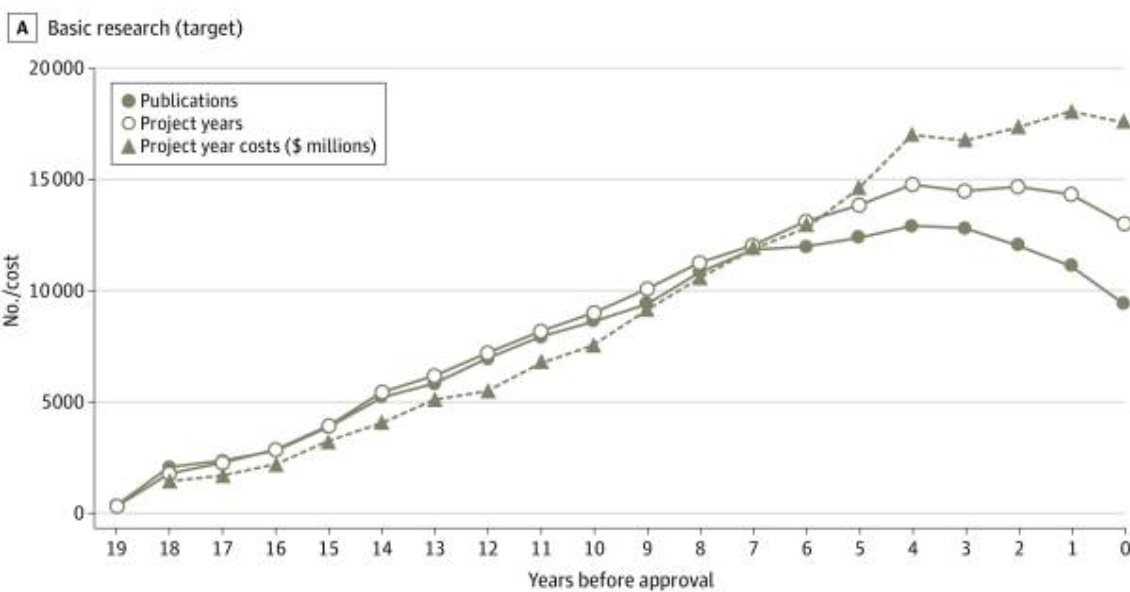

I think what Cook-Deegan was diagnosing back then—and what’s now become painfully visible—is the breakdown in translation between the world NIH was designed for and the one we actually live in. The old narrative—fund science, cure disease—was elegant, linear, legible. But in practice - it’s never really worked that way. Progress comes in long, strange arcs. The clinical payoff of basic research is often two decades downstream, delivered through five institutions and three companies with a dozen forgotten names along the way.

GLP-1 agonists are a perfect case study: everyone wants credit, but that depends on how we define research, translation, and value itself. Their roots stretch back over a century—from the first inklings of gut hormones in 1906, through decades of incretin biology, to pharma’s eventual translational breakthrough. Who gets credit? NIH? Academia? Industry? The truth is messier: we built a miracle from a century of nonlinear contributions—and then priced it at $900 a month.

So when someone asks, “how much of basic research is funded by NIH?” I want to say: define basic, define research, define value. Are we counting publications? Patents? FDA approvals? Lives saved—or lives merely prolonged? Is the goal to reduce DALYs, to extend healthspan, or to maximize the optionality of the species?

The NIH can’t answer that question. Neither can I. Because the NIH isn’t built to give answers—it’s a distributed system of epistemic insurance. It’s built to keep asking. It’s not a pharma pipeline––it’s a safety net. A sprawling, messy bet on the idea that if we fund enough smart people for long enough… something important will happen. We don’t fund it because we know what’s coming; we fund it because we don’t.

And yet: I still think it matters which parts of NIH are working. It matters that NHLBI research has helped slash U.S. cardiovascular disease deaths by 60% since 1999; or that NIAID helped transform HIV from a death sentence to a chronic condition; or that intramural research—only 10% of the budget—has enabled dozens of FDA approvals, and that the Common Fund has an 8x higher patent yield per dollar than standard R01s.

And it matters, too, that some institutes have quietly absorbed billions with surprisingly little to show for it. Not because their missions are unworthy, but because NIH’s structure—sprawling, overlapping, sacred—has drifted out of alignment with the world it’s trying to serve.

Take addiction: NIDA and NIAAA continue to operate as separate fiefdoms, even though most patients don’t separate alcohol from opioids, and most neuroscience doesn’t either. Or Alzheimer’s: divided for decades between NIA and NINDS. One framed it as aging, the other as neurodegeneration. Same disease, same patients—but different narratives, different panels, different language. Researchers rewrote the same grants to suit each frame. And while AMP-AD and others have tried to close the gap, the divide still echoes through the way studies are funded, interpreted, and translated.

And clinical trial infrastructure? It's exactly as messy as you'd expect from a system built by 27 institutes, each with their own processes, priorities, and preferred acronyms—IRBs, SOPs, DSMBs, CTSA hubs; fuck, even describing it risks sounding like the problem. A researcher trying to launch a trial across Alzheimer’s and stroke might as well be trying to build a bridge between warring city-states—complete with independent review boards (plural), contract negotiations that feel like Cold War diplomacy, and the creeping realization that most of the delay isn’t scientific—it’s structural. NIH has the Trial Innovation Network, sure, and it was supposed to fix this. But talk to anyone actually in the weeds and they'll tell you it still feels like building a rocketship out of grant forms and good intentions.

Still, contradiction is part of the story. Because just as NIH’s diffusion sometimes dulls its edge, that same breadth creates fertile ground for scientific spillover. Between 2010 and 2016, of all the NIH funding tied to the 59 cancer drugs approved in that window, only 31% came from the National Cancer Institute. The rest came from elsewhere—grants aimed at immunology, endocrinology, or systems that, on the surface, had nothing to do with cancer at all. This is the NIH paradox: redundancy can waste money, but redundancy can also save lives.

That’s why programs like the NIH Common Fund feel so vital. Designed as venture-style investments, they cut across silos, fund riskier ideas, and emphasize measurable impact. They allow for small bets with big leverage. And in a system where tens of billions flow through legacy pathways, one can hope these things will survive through natural selection: leaner, faster, more self-aware.

And yet, even the standard NIH grant—the humble R01—is no less essential. It's the scaffolding of American science. The long tail. It funds the unnoticed, the incremental, the not-yet-relevant. Cancer immunotherapy and CRISPR didn’t emerge from moonshots—they came from slow-burning knowledge assembled by thousands of investigators over decades. The NIH isn’t just a funder of breakthroughs; it’s the soil that makes them possible.

But when that soil becomes overgrown—when legacy outweighs logic—it stops feeling like a research system and starts feeling like a relic. A cathedral that forgets it’s also supposed to be a lab.

These aren't just accounting artifacts - they're signs that some parts of the machine are tuned for the world we’re living in, and others are coasting on legacy and unfulfilled promise. The NIH, like any institution, has sacred cows. And maybe it's time we ask whether all 27 institutes still deserve to exist in their current form.1

Public health experts can keep trying to revive the old lines—cures are just around the corner, science is the engine of progress, this time we really mean it—but it doesn’t land. The story feels like a rerun. The glow is gone. And the more we shout about miracles, the more people stop believing. Because in 2025, we live in the afterburn of too many overpromises: Alzheimer's drugs that failed, cancer cures that never came, pandemic prevention plans that collapsed on contact with reality.

So what now?

We don’t need less NIH—just a smarter one. One that knows when to stop protecting its kindred. If we can measure how many healthy years of life we save per dollar spent—DALYs-per-dollar—we can start to see which programs are truly saving lives and which are just preserving turf. We can admit that some of the NIH's worst-performing institutes are failing not because their problems are intractable, but because they've become too comfortable failing. We can stop pretending that every disease deserves equal attention, or that every NIH grant is equally sacred.

If NIH wants to win back trust, it needs to stop acting like a cathedral and start acting like a lab again. That means exposing failure—real failure—not dressing it up in the language of promise. It means knowing when a hypothesis is dead and not embalming it in grant cycles. The beta-amyloid mess wasn’t just a scientific wrong turn—it was a systems failure; a refusal to walk away.

And no, this isn’t about funding less. It’s about lowering the activation energy for actual experimentation. Making it cheap—absurdly cheap—to test things. To try, fail, and try again without needing a 40-page PDF and six months of review. That means building systems where the experiment costs less than the meeting to approve it. Where doing the work is easier than defending the idea.

Sure, we still need space for the long arc—the basic science that stumbles sideways into something profound. But we also need to stop pouring money into projects that can’t explain what success looks like. Public health isn’t a shrine. It’s a sandbox. And the whole point of a sandbox is that you can knock things over.

That shift—from reverence to experimentation—is what NIH must embrace. Until then, NIH will keep doing what it’s always done: funding the present to buy a better future—quietly, imperfectly, invisibly. But even the most enduring institutions must learn to bend with time. Not to chase fashion, but to remain legible. To stay rooted in purpose, yet open to reinvention. Because belief fades when the story stands still.

Okay, yes—this is me doing exactly what I said I wouldn’t do. I know. I opened with all that stuff about narrative loss and epistemic fog and how I wasn’t going to reduce it to a list of budget tweaks or ROI metrics, and now here I am proposing... budget tweaks and ROI metrics. It’s embarrassing - or at least, mildly soul-crushing. But also maybe inevitable? Because once you start poking at the NIH long enough, the temptation to fix it—like, systemically, cleanly, with charts—is weirdly hard to resist. Even if you know better. Even if you suspect the whole point is that it can’t be clean. And maybe the real problem is that I want the piece to both feel like fog and resolve like a TED Talk. Which is... not how reality works. So yes, I see the contradiction. I’m inside it.