The Pageant of Responsible Longevity

On the quiet horror of healthspan science and its desperate decorum

It always starts the same way.

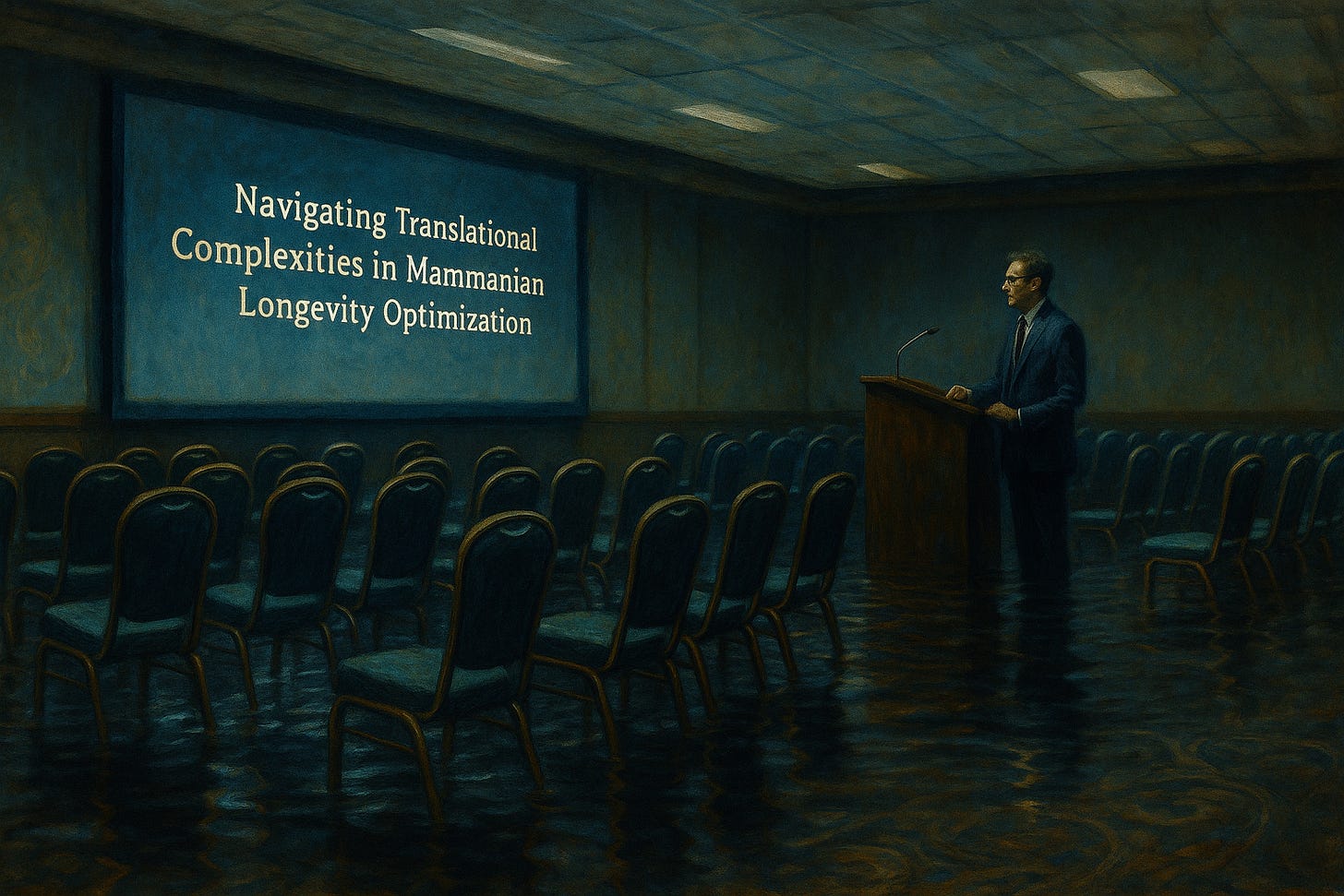

You are sitting in a carpeted conference center ballroom, the carpet itself a mosaic of muted paisleys chosen less for aesthetic appeal than for its ability to conceal vomit1, blood, and the slow accumulation of dead skin cells shed by generations of conference-goers who came before you to listen to remarkably similar talks. The industrial-grade air circulation system produces a white noise just loud enough to make you strain slightly to hear, just quiet enough to avoid complaint—the acoustic equivalent of learned helplessness. Before you unfolds the annual theater of Responsible Optimism in Aging Research™, presented by the Institute for Incrementalist Approaches to Mortality Mitigation.

There are men and women wearing blazers in the new style: performance-fabric ("moisture-wicking" is the proprietary terminology they prefer, as if human perspiration were classified as an industrial contaminant requiring OSHA-approved remediation protocols), available in one of three deeply responsible shades (Oatmeal, Charcoal, Tech-Blue—the holy trinity of non-committal professionalism). There are framed badges swinging from lanyards2, slightly too many podcast microphones (modern-day phylacteries storing captured wisdom for distribution to the digital faithful), carefully manicured LinkedIn profiles being exchanged via proprietary apps that have replaced the already-abstract ritual of business card exchange with something even more ethereal and less human.

The panels have names like:

"Post-Lifespan Terminal Trajectory Management: Optimizing Metrics for End-Stage Vitality in the Context of Inevitable Systemic Decline"

(translation: dying slightly better)

"Epistemological Cartography at the Interfaces of Translational Geroscience: Foundational Frameworks for Multi-Stakeholder Navigation of Uncertainty Domains"

(translation: we don't know what we're doing but we've created a complex vocabulary to discuss our ignorance)

"Building Epistemic Bridges (Literally): Infrastructure as Metaphor for Incremental Progress in Life Extension Research"

(featuring an actual architect who designs physical bridges alongside a bioethicist who has published six papers on "bridging divides" without ever specifying what exists on either side of said divides)

"Emerging Ethical Frontiers in Murine-to-Human Translational Confidence-Building Measures: A Post-Colonial Perspective"

(which somehow manages to appropriate social justice terminology while advancing the interests of well-funded research institutions)

The speakers—and you have seen them before, you have seen their tweets and their cautious New York Times essays and their haunted eyes that betray, in unguarded microseconds between slides, the desperate animal terror they've spent entire careers intellectualizing away—are an exquisite subgenus of grifter: not the snake-oil men of old with their traveling medicine shows and painfully obvious deceptions, nor the doomsday biohackers with syringes of unregulated NAD+ and the feverish messianic gleam of someone who's read exactly one book about the science of aging3, but the Virtuous Anti-Hype Hypemen. The Professional Moderates™. The Designated Adults In Various Rooms.

They are the ones who will tell you, gravely, that defeating death by 2030 is unrealistic4. They will smirk at Aubrey de Grey, at David Sinclair, at whichever obvious target is deemed acceptable that year in the way that medieval villagers might have smirked at the local madman—a necessary social function for defining the boundaries of acceptable discourse. One speaker—a tenured professor whose entire career consists of publishing papers arguing that other people's ideas about aging intervention are premature—actually uses the phrase "Appropriate Chronological Horizon Management" to describe what normal humans would call "not getting our hopes up too much."

They are, in short, the hall monitors of ambition. The TSA agents of the imagination, confiscating intellectual contraband that exceeds the allowed limits of 3.4 ounces of hope per conceptual container. They are there not to dream, or to build, or even to meaningfully tear down. They are there to preserve the decorum of dreaming. To ensure that our collective yearning for more life doesn't exceed the bounds of good taste. To make certain that the conference coffee break starts precisely on time, because adherence to schedule is the last refuge of those who have abandoned all larger purpose.

They wear their moderation like a boutonnière, a visible signal of their allegiance to what they call "intellectual rigor" but what is, in fact, a kind of tepid cowardice so deep it has metamorphosed into an aesthetic. A lifestyle. A brand.

You look at them, the whole squirming herd of them, adjusting their wireless presentation clickers and clearing their throats before uttering yet another variation on "the data are promising, but much work remains to be done," and you feel a peculiar kind of sadness. Not because they're malevolent. Because they're so small. Because the future—the actual future, the roaring, terrifying, unknowable future where humans might transcend their biological constraints or fail catastrophically in the attempt—will not be brokered by these careful people with their carefully starched ethical frameworks and their carefully hemmed imaginations.

On the second day, during a mid-morning panel called "Metrics of Mortality Compression in Post-Retirement Populations: Toward a Framework for Benchmarking Later-Life Quality Indicators," you witness something unexpected. A panelist—a woman in her fifties with the standard-issue conference blazer (Oatmeal variant) and sensible ergonomic glasses—momentarily drops her guard.

She's mid-sentence, discussing "cohort analysis methodologies for segmenting intervention response profiles," when something catches in her voice. The PowerPoint slide behind her shows a perfectly reasonable graph with a perfectly reasonable p-value and a perfectly reasonable asterisk indicating statistical significance according to perfectly reasonable pre-established criteria. But her voice—just for a moment, less than a second—fractures like thin ice on a pond.

The audience doesn't notice. They're checking email on their phones or thinking about which concurrent session to attend next or wondering if the lunch buffet will include those little pastry things from yesterday.

But you see it. The momentary crack in the wall. The brief intrusion of actual humanity into the proceedings. Her eyes flick toward the exit door at the side of the ballroom—a glance so quick it's almost subliminal—as if gauging the distance to escape. Then she clears her throat, re-establishes eye contact with the middle distance, and continues her sentence as if nothing had happened: "...which allows for more granular assessment of intervention efficacy across demographic strata."

And the moment is gone. The mask is back in place. No one else seems to have noticed. But you can't stop thinking about that fragment of a second—that tiny window into what might be happening beneath the surface of every single person in this room. That glimpse of the terrified animal hiding behind the PowerPoint slides and jargon and careful, careful moderation.

If you stay long enough—past the first panel, past the "fireside chat" with the venture capitalist whose tan suggests a complex relationship with solar radiation, past the coffee break where the coffee tastes faintly of the cardboard cups it's served in, a taste that somehow perfectly complements the intellectual cardboard being served on stage—you begin to notice a different pattern unfolding, a deeper failure: The epistemic rot beneath the marketing.

These people love papers. God, do they love papers. They wave them around like civil defense pamphlets from the 1950s instructing you, earnestly and absurdly, to take shelter beneath your desk as the mushroom cloud blooms outside the classroom window. "In a recent Cell Reports study—" "Preliminary work in non-human primates suggests—" "A promising result from a phase 1b trial—" "New analysis shows methylation drift is reversible in certain tissue contexts under specific experimental conditions when controlling for circadian influence—"

Each phrase delivered with the strained confidence of an air raid warden calmly advising that the atomic blast will be quite manageable if you just keep your head down and eyes closed. The audience nods along, not because they believe it will work, but because performing belief has become part of the emergency procedure. They collect citations and abstracts like radiation badges—small, tidy, inadequate talismans to reassure themselves they’ll survive a catastrophe no one truly knows how to prevent.

What they do not do—ever, not once, not even accidentally—is read the methods sections5. They do not ask the heretical questions:

How were the endpoints defined? (And redefined mid-study when the original endpoints weren't being met? And then subjected to what they call "exploratory analysis" but what a casino would call "trying different slot machines until one pays out"?)

How were the controls chosen? (And were they actually appropriate comparators, or convenient straw men selected precisely because they would make the intervention look better? Did the control mice live in the same room as the treatment mice, or were they housed separately, subject to different noise levels, different microbiomes, different graduate student handlers?)

Were the p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons? (Or did the authors engage in what statisticians politely term "p-hacking" and what the rest of us might call "statistical grave robbery"—digging through the data until they find something, anything, to justify the research grant?)

When did the curves start to separate? (And was that timing pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan—or noticed only after the fact, like a magician discovering a "chosen" card that was carefully forced from the start? And how many other places were they almost willing to declare separation, if only the Kaplan-Meier gods had been more cooperative?)

They do not wrestle with the soft underbelly of the paper—the duct-tape realities of small sample sizes, post-hoc subgroup slicing, vague endpoints rebranded as "exploratory outcomes," the thousand little compromises that transform the messy reality of biological investigation into the clean lines of a publishable manuscript.

They accept the Discussion section at face value, like tourists accepting a tour guide's simplified explanation of complex cultural artifacts. They wander the gift shop of scientific publishing, collecting attractive souvenirs—glossy civil-defense booklets promising safety in tidy bullet points—without ever confronting the horror lurking just outside the blast radius of their carefully managed rhetoric.

Papers as emergency instructions. Papers as fallout shelters built from plywood and wishful thinking. Papers as social proof that their optimism is not mere optimism, but government-certified, peer-reviewed optimism. Optimism tested and rated against theoretical blast pressures™.

The ritual reaches its apex during the "Consensus-Building Workshop on Forward-Looking Terminology in Age-Related Decline Management," where twenty-seven participants spend ninety minutes debating whether to use the phrase "healthspan enhancement" or "health extension" in a forthcoming white paper that no one outside this room will ever read. The moderator—a specialist in what she terms "linguistic navigation of bioethical complexity domains"—manages the discussion with the solemn gravitas of a civil defense official explaining precisely how thick your concrete basement ceiling must be to withstand nuclear fallout.

"We must consider," she intones, adjusting her Tech-Blue blazer with practiced precision, "the semiotic implications of our terminological frameworks. The phrase 'health extension' may inadvertently privilege duration over quality in our conceptual mapping of intervention outcomes."

The audience nods. Of course. Of course. How could they have been so careless as to privilege duration over quality in their conceptual mapping? A grave error indeed.

"Whereas 'healthspan enhancement,'" she continues, "foregrounds the qualitative dimensions of our research objectives while maintaining temporal neutrality vis-à-vis intervention endpoints."

More nodding. A man three rows ahead of you is taking detailed notes, his fingers moving across his tablet with the reverent precision of a monk illuminating a manuscript.

You realize: This is not a scientific discussion. This is not even a policy discussion. This is an emergency drill.

A Duck-and-Cover rehearsal against the slow, inevitable blast wave of aging and death. A pageant of preparedness for a disaster that everyone knows, somewhere deep down, cannot actually be survived.

You watch it happening in real time: The panel moderator, wearing a dress shirt that clung just slightly too tightly to his frame — the uniform of a man who half-expects to bench-press his credibility if challenged — teeing up a "discussion" on "realistic timelines for translation." The inevitable deferment to "what the data show"—without the slightest flicker of recognition that data do not "show" anything without interpretation, without statistical manipulation, without the imposition of narrative onto numbers.

At one point, a brave soul from the audience—clearly not a regular at these events, perhaps a graduate student who hasn't yet been properly socialized into the norms of the field—asks a question that momentarily pierces the veil:

"But if all these interventions only extend life by a few years, aren't we just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic? Shouldn't we be pursuing more radical approaches to the fundamental mechanisms of aging?"

The silence that follows is exquisite. The panelists exchange glances, a silent negotiation over who will handle this breach of protocol. Finally, the most senior among them—a distinguished professor with silver hair and a custom blazer that transcends the standard trinity of approved colors—leans toward his microphone.

"That's an interesting question," he says, deploying the standard academic euphemism for "you have violated an unspoken taboo." "We have to be very careful about setting appropriate expectations." His voice adopts the tone one might use to gently correct a child who has inadvertently said something racist at a dinner party. "Radical approaches, as you call them, often fail to appreciate the complex homeostatic mechanisms that have evolved over millions of years. Our focus on incremental, evidence-based interventions reflects not a lack of ambition but a respect for biological reality."

Translation: How dare you suggest we might actually try to solve the problem we claim to be working on?

The questioner shrinks in their seat. The audience resumes its gentle nodding. The natural order is restored.

It is only by the third or fourth panel—around the time someone is earnestly saying the phrase "multi-stakeholder translational ecosystem dynamics" without irony, without the slightest awareness that they are speaking in a kind of corporate glossolalia—that you begin to fully grasp the bleakness of their future.

Because they do have a future to sell. Oh yes. They have spent entire afternoons cross-referencing abstracts and LinkedIn thought-leader posts and have stitched together a Vision, capital V.

And the Vision goes something like this:

More people will get their "biological age" clocked annually, like an oil change. They will receive a PDF report with traffic-light colored indicators of various biomarkers, which they will skim before filing away electronically, experiencing a vague sense of virtue or anxiety depending on whether their methylation patterns are deemed appropriate for their chronological age. (The company providing these reports will be acquired by a slightly larger company, which will be acquired by a significantly larger company, which will eventually be acquired by Amazon, after which the service will be free with Prime membership but the data will be used to optimize adult diaper advertisements.)

More aging interventions will "extend healthspan" by marginal amounts. These gains will be celebrated at subsequent conferences with PowerPoint slides showing Kaplan-Meier curves with slightly less steep descents, prompting polite applause from audiences who will go on to die exactly as their parents did, only with more data points collected along the decline.

More predictive biomarkers will allow slightly earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer's, cancer, cardiovascular disease—which will still kill you, just on a slightly more convenient schedule and with greater precision in the billing codes used to extract maximum insurance reimbursement during your precisely measured decline.

You will receive notifications like:

"You have entered Terminal Trajectory Path 7B: Enhanced-Awareness Cognitive Decline with Moderate Velocity. Recommended interventions include Subscription Package Gold (autopay only) and consultation with our Optimal End-Stage Experience Navigation Specialists."

"Your Projected Mortality Window has been updated to Q3 2058 (±4.7 months). Would you like to pre-authorize Advanced Directive Package Silver or Premium? Premium users receive priority palliative care triage and complimentary memorial service slide presentation templates for their loved ones."

"Congratulations! Your Bodily Decomposition Optimization score has improved by 3.7 points this quarter. At current rates, your remains will achieve 62% greater biodegradability than the baseline population, qualifying you for our Green Passage™ carbon-neutral interment program."

It is, when you step back from the 72-inch display showing the PowerPoint deck about "The Future of Aging," the most spiritually impoverished "vision" imaginable. A future where the major upgrade over the present is:

marginally better Kaplan-Meier curves (which still, tellingly, end at zero percent survival)

a slightly more medicalized vocabulary for describing the same processes of decay that have claimed every human who has ever lived

an increased market for subscription-based epigenetic consulting services (billed quarterly, with enterprise pricing available for forward-thinking corporations concerned about their aging workforce)

The future, according to them, is an elaborate CRM platform for human bodies, sending out automated reminders for various maintenance procedures that ultimately cannot prevent system failure.

A future where your life, extended by actuarial rigor and meticulous attention to your n-of-1 biomarkers, concludes in a moderately more optimized assisted living facility, with 14% fewer pressure ulcers and a smart mattress that adjusts its firmness according to your declining sarcopenic metrics.

A future without transcendence. Without awe. Without even the honesty of despair.

A future carefully hemmed and trimmed and optimized until it resembles a waiting room where no one knows what they are waiting for anymore, only that it is important to be very well-behaved when it arrives. A future where death has been medicalized, optimized, quantified, and branded—but never actually confronted.

At last—after the citations, the biomarkers, the panels moderated by venture capitalists whose personal anti-aging regimens involve young blood transfusions they're careful not to mention in these professional contexts—you reach the center of the thing.

There, at the core of all their careful hedging and credentialed modesty, at the foundation of their cautious hope and deferential living, you find fear.

Old, raw, soft-palmed fear.

Not just fear of death. Fear of feeling the fear.

At night, after the conference sessions end, when they return to their identical hotel rooms with their identical laminate desks and identical shower-shampoo dispensers, do they feel it then? When the PowerPoint slides are closed and the email replies are sent and the miniature bottles from the minibar are empty—in that moment before sleep, do they sense it? The vast, cavernous nothing that awaits? The biological obscenity of consciousness evaporating? The absolute indifference of the universe to their carefully managed biomarkers?

For just a moment, you imagine you can see it: Behind the eyes of the panelist now discussing "Quality-Adjusted Life Year metrics in comparative intervention assessment" is a vast dark lake. The surface of the lake is perfectly, unnaturally still. But beneath that surface—miles beneath, in the lightless depths where pressure crushes even bone—something ancient and terrible stirs. A leviathan of pure animal terror. The knowledge that all of this—the blazers, the PowerPoints, the polite applause, the LinkedIn profiles, the funding applications, the journal citations—is ultimately a child's game played in the shadow of an oncoming freight train.

And then the moment passes. The panelist continues their sentence. The audience continues its nodding. The ritual continues.

They cannot bear the thought that science—their beloved science, their safety net of abstracts and graphs and probability intervals—might be helpless before death's blank, hot, airless wall. That all their careful moderation, all their responsible optimism, all their epistemic humility might be not wisdom but merely the most elaborate form of cowardice ever devised.

And so they build rituals to keep themselves busy.

Rituals of cautious optimism.

Rituals of Responsible Citation.

Rituals of Anti-Hype Panels.

And every one of these activities is the same simple animal prayer:

Do not make me feel it.

Do not make me see it.

Do not make me know.

And here you sit among them, watching the PowerPoint transitions dissolve one slide into another, they perform their perform their tabletop rehearsals for a defeat they cannot prevent: tabletop exercises in which no one ever wins, but everyone is required to participate—while outside, beyond the hermetically sealed conference doors, Death waits with infinite patience, unimpressed by their credentials, unmoved by their graphs, ready to collect them exactly as scheduled, give or take 2.7 years of statistically significant healthspan extension (p < 0.05, n = 7, mice only, results not replicated).

The vomit in question being not the consequence of actual human excess or illness but rather the symbolic regurgitation of half-digested talking points—as in "I'm excited to share that our Phase 1 safety data demonstrated no significant adverse events when adjusted for multiple comparisons and baseline covariates, suggesting a promising though preliminary path forward pending further investigation in larger cohorts"—a sentence which upon careful inspection contains precisely zero actual content yet somehow requires eighteen PowerPoint slides to explicate.

The badges themselves constitute a complex semiotic system: job title positioned above name (hierarchy of identity), institutional affiliation in slightly smaller font (source of credentialing), and—for the especially privileged—a colored stripe along the bottom edge signifying "Speaker" or "Panelist" or "Organizing Committee" (the secular equivalent of ecclesiastical vestments differentiating cardinals from bishops from mere priests).

The book in question? “Lifespan”, by David Sinclair. It’s always “Lifespan”.

And yet somehow plausible enough to warrant an entire panel discussion and media blitz declaring it unrealistic. Consider the curious logical structure: "X is so patently absurd that we must spend considerable resources explaining why it's absurd"—a rhetorical move that betrays the anxious underbelly of their supposed certainty. Compare: "Discussing whether invisible leprechauns control the stock market is ridiculous and irresponsible" (a statement no one feels compelled to make because actual absurdities require no such disclaimers).

The Methods section of a scientific paper is, of course, where all the actual information lives—where the authors confess, in miniature font and technical language, all the compromises, corner-cutting, and conceptual duct-tape that held their experiment together long enough to extract a p-value worthy of the Discussion section's grandiose claims. It's where you learn that the "significant lifespan extension" trumpeted in the abstract was achieved by excluding animals that died in the first three months as "early mortalities unrelated to the intervention," or that the control group received a subtly different diet than the treatment group, or that the sample size was determined not by power analysis but by "how many mice we had budget for."

Enjoyed the humor here.

Really well written piece, I enjoyed it a lot!